A Glimpse into the Tidelands of North Carolina with the Natural Infrastructure Lab

For the last year and a half, a collaboration of researchers and designers have been working together on a project called Tidelands — studying, developing and pioneering new forms of natural infrastructure — approaches that use nature to address the challenges related to sea-level rise, erosion, flooding, and habitat loss in the nation's bays and estuaries.

Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Virginia Brian Davis who codirects the Natural Infrastructure Lab (NIL) is part of this team conducting research supported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Engineering with Nature (EWN) Program. Davis leads UVA-based researchers who are working together to study and identify best practices and future solutions in natural infrastructure for the mid-Atlantic and Southeast United States. Partner labs at the University of Pennsylvania (EM Lab) and Auburn University (LIDL) are examining the Northeast and Gulf Coast regions, respectively, stitching together a wide geographic area to be able to share findings with landscape architects and engineers across an expansive coastal territory.

|

Image

|

Image

|

|

Image

|

Image

|

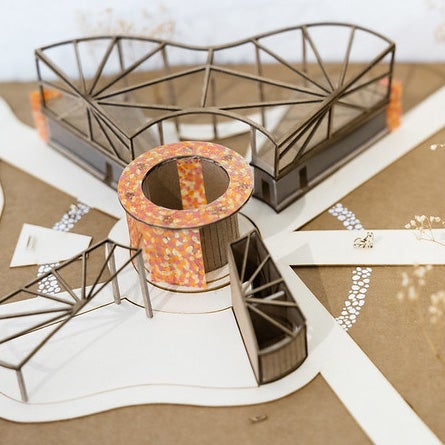

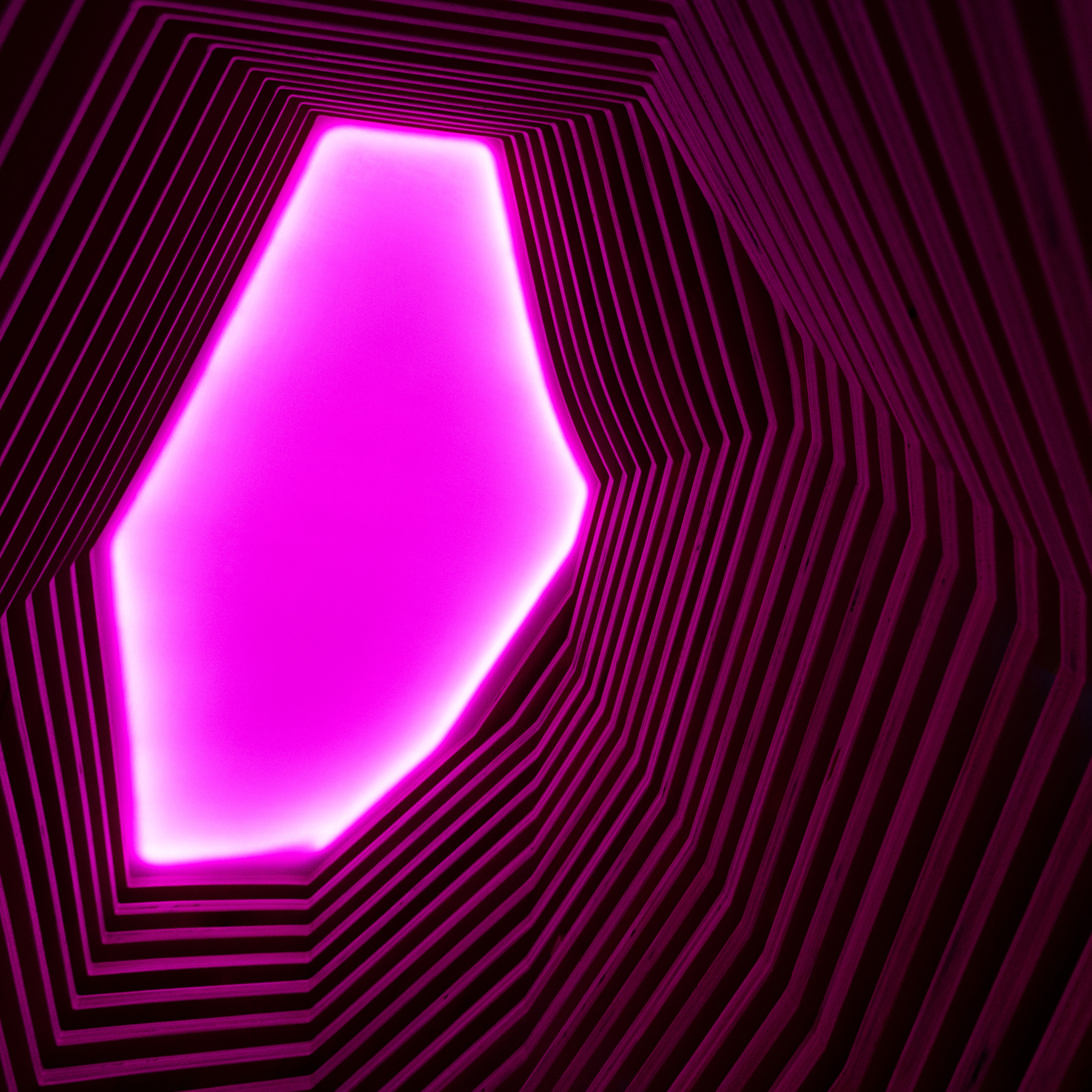

| The Natural Infrastructure Lab (NIL) commenced the Tidelands research project to produce natural infrastructure design concepts on the mid-Atlantic and Southeast coasts. Images by NIL. | |

Tidelands aims to understand what forms of natural infrastructure are possible in the nation's bays and estuaries, to identify which forms are most desirable, and to translate that knowledge into principles that drive natural infrastructure design innovation. Research projects like the one Davis is leading are helping to assess how maintaining and restoring natural infrastructure to support healthy functioning can save money, time, habitats and lives in both the short and long-term future. Davis said, "Even beyond pressures of development, one thing our society has consistently agreed upon is the need for innovation in infrastructure, especially water infrastructure. The practice of landscape architecture has a natural place in this area of research and application."

There are technological approaches that already exist, but nature provides many more models we can learn from — that's our goal, to learn from nature and create new innovative forms of infrastructure. — Brian Davis

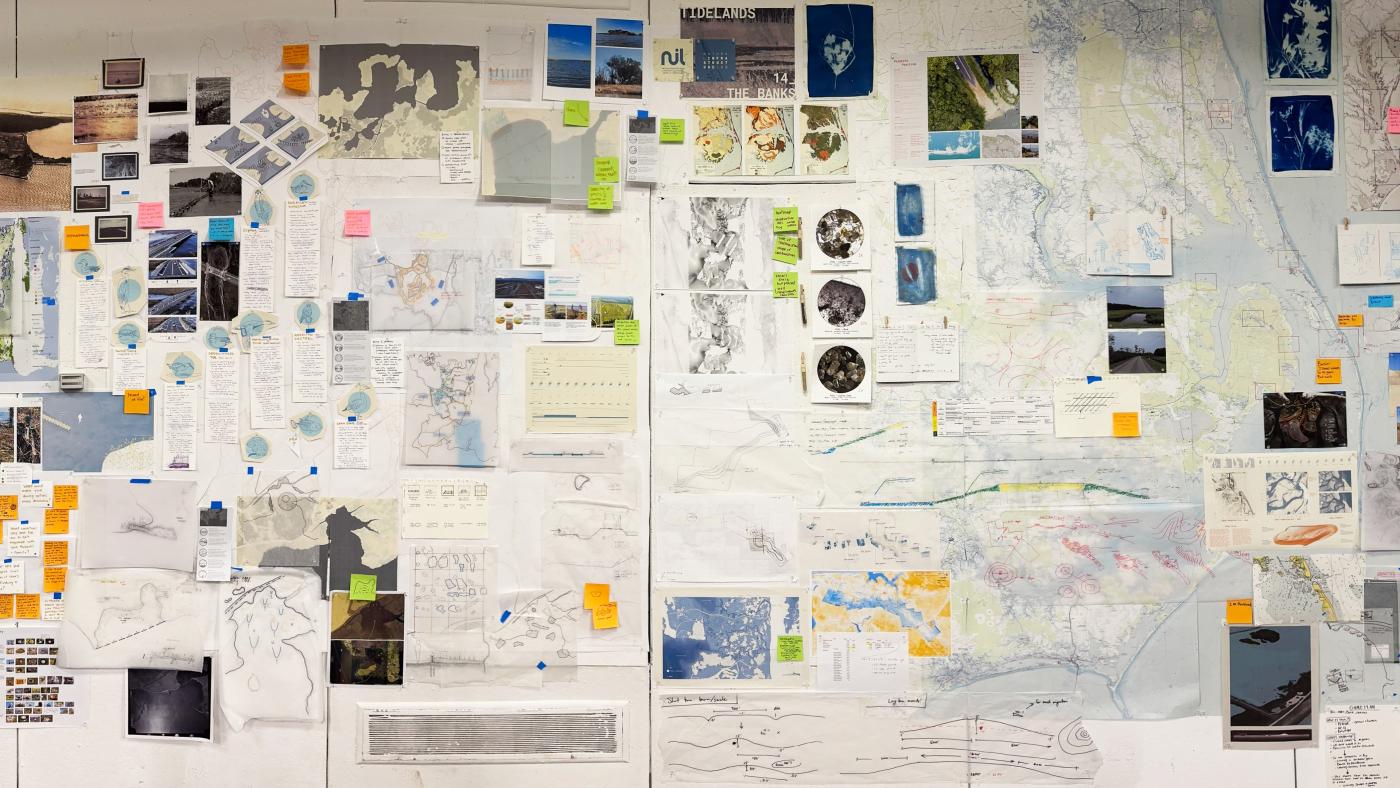

On display at the School of Architecture's Campbell Hall through November 7, an exhibition titled NIL_The Banks: A Glimpse into the Tidelands of North Carolina curated by the NIL team presents the research project, focusing on both the working processes and key findings.

A Glimpse into The Banks

In a research presentation held at the School of Architecture, project manager Ruby Zielinski shared how the project began. Through a workshop held at partner school Auburn University, experts and stakeholders, including ecologists, geologists, engineers, community partners and designers, came together to ask a fundamental question: where should we be working? The Auburn team began categorizing the coasts, identifying similarities and differences of conditions and eventually naming 32 "estuary units" along the water's edge. Using a wealth of geological, ecological and socioeconomic datasets, the units identified areas where common land uses, ecosystems, and natural processes align.

By spanning a diverse set of landscapes, we are able to tackle different issues at many scales. Some places are more rural and some are more urban. Some have dramatic tide ranges, and some are subtle. This ensures that our design approaches reflect the diversity of estuary conditions along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. — Ruby Zielinski

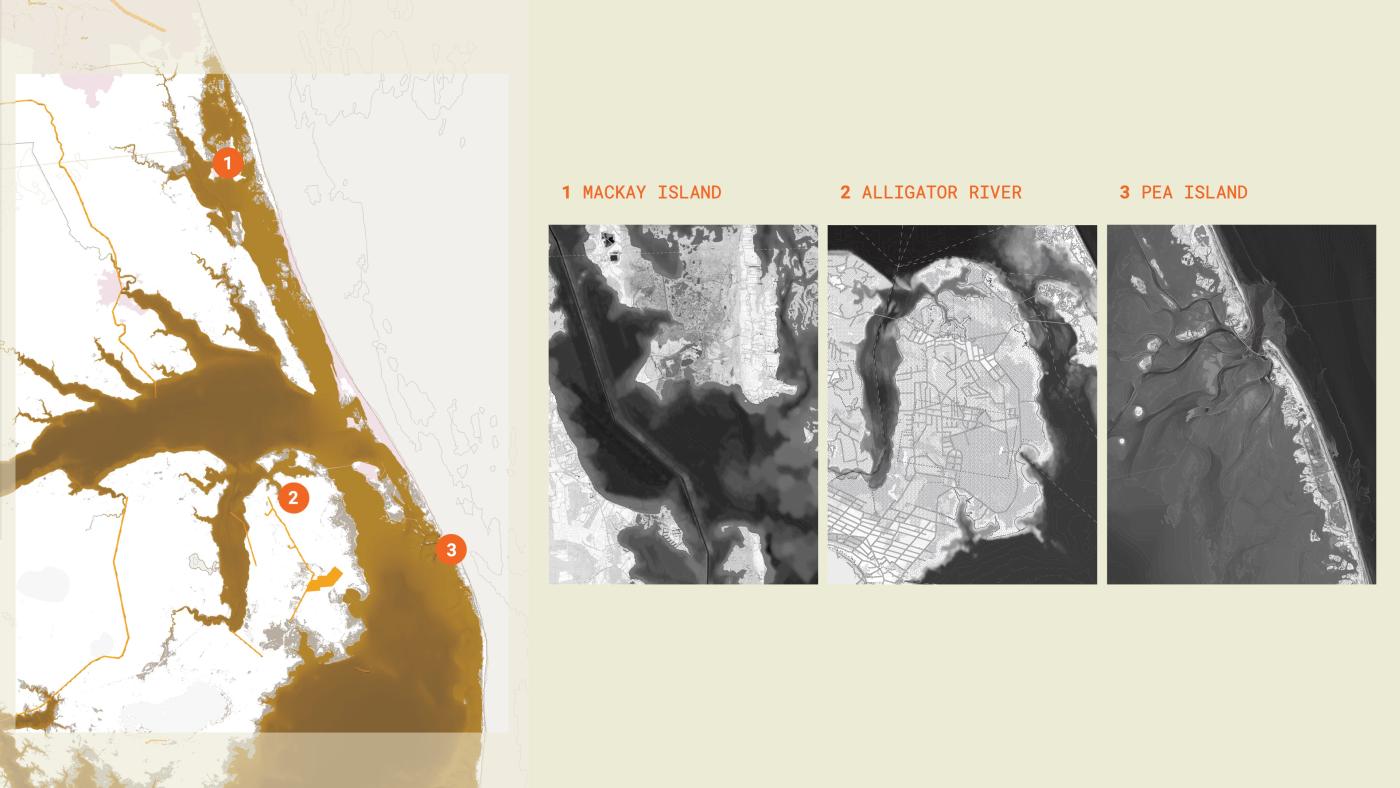

NIL at UVA focuses on the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary, the second-largest estuarine system in the United States covering over 3,000 square miles of water and encompassing numerous sounds. Located in northeastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia, the system is a vital resource for industries, including commercial and recreational fishing, and for communities of people and wildlife. Their research examines three specific sites in the Outer Banks, a barrier island chain that shelters the estuary, with inlets that connect the estuary to the ocean: MacKay Island, Alligator River, and Pea Island.

|

Image

|

Image

|

|

Image

|

Image

|

| NIL Co-director Associate Professor Brian Davis (top right) and Design Research Intern William Riedlinger (bottom left) share Tidelands research findings. Photos by Tom Daly. | |

The Process of Design Research, Fast and Slow

Research associate Adrian Robins explained NIL's process, one that includes methods he describes as both "fast" and "slow," "precise" and "exploratory," "quantitative" and "qualitative." After identifying the larger area of inquiry, Robins and Zielinski embarked on a site visit, getting the opportunity to meet with and survey the area with staff members of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, including project partner Fred Wurster. Wurster presented locations where the Fish and Wildlife Service staff were looking to apply nature-based solutions, and from there the three specific research sites emerged. MacKay Island, Alligator River, and Pea Island are three of the eleven designated National Wildlife Refuges on the Outer Banks, ensuring a commitment to habitat conservation and management.

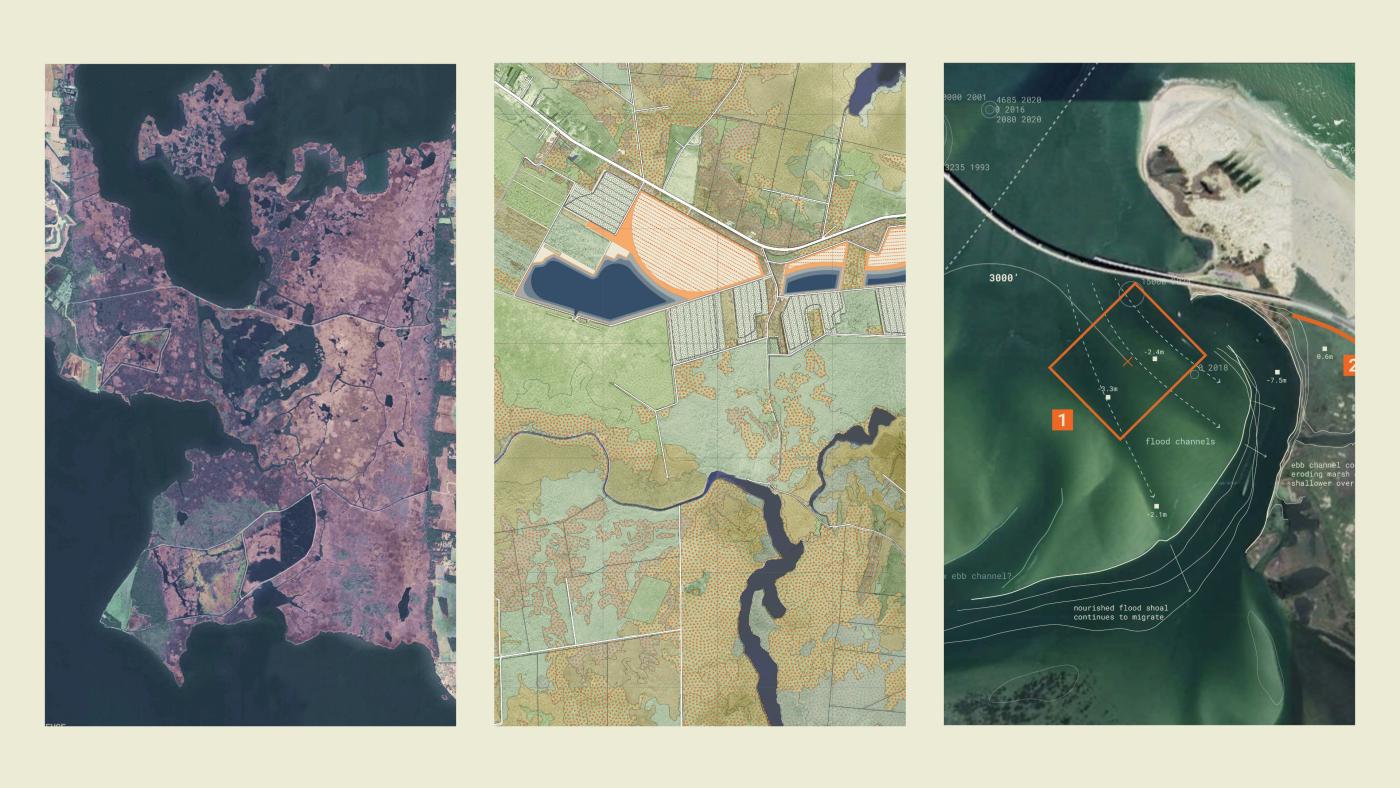

Time on-site, providing first hand experiences of each place, included various research methods like aerial imagery captured by drones, RTK, and LiDAR; in-situ sketching; and collecting soil and plant samples. This was a crucial "jumping off point" according to Robins and an important methodological beginning: starting with the place itself and noticing how the landscape behaves. Upon returning to UVA, the team began to merge their documentation and observations with datasets, such as geospatial data, including sea-level rise projections, hydrology, and historic topography.

Pairing the qualitative and quantitative inputs with precedents at multiple scales, the team then developed a series of design scenarios using various 3D modeling software, testing how different kinds of natural forms would alter the landscape, especially over long periods of time. At MacKay Island, for example, by studying overlays of wind, wave, and current data, the team began to think about how to leverage natural processes already in place. "We are testing and exploring how small changes can have larger effects over time," said Robins. "We do that through both drawing and analysis — both are reciprocal and equal parts of the design research process. We analyze, design, reanalyze, redraw — and then repeat."

The research is not just about acquiring data, but also engages other approaches to how we measure, draw, and ask questions about landscapes. It's adaptive and cyclical which lets us keep refining, learning from both data and intuition. — Adrian Robins

The team's work relies on thinking through time, not just space. They use a mathematical model called Sea Level Affecting Marshes Model (SLAMM) created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to simulate potential impacts of long-term sea level rise on wetlands and shorelines. Pairing SLAMM with historic imagery, the researchers are able to visualize marsh behavior, including migration patterns and how overwash reshapes barrier islands. The time-based view provides important contextual cues that then allow, as the team describes, "to design projects that can evolve gracefully."

A Landscape of Continuous Motion

The barrier islands of the Outer Banks are dynamic forms that change constantly in response to natural processes like wind, storms, wave action, and rising sea levels. As sea level rises and waves push them south, the islands migrate both inland and southward. On Pea Island, one of the team's site of investigation, that migration can reach as much as fifteen feet per year. Natural Infrastructure Lab design research intern and landscape architecture graduate student William Riedlinger explained, "These landscapes are in continual motion. Traditionally, coastal protection has focused on holding the islands still — through breakwaters, terminal groins, and other forms of grey infrastructure. While these methods can work for a period of time, they interrupt the sediment cycles that allow the islands to live, and often accelerate erosion."

Our approach, by contrast, uses natural infrastructure to buy time for communities — slowing down natural processes without stopping them entirely. — William Riedlinger

NIL's strategy also takes wildlife habitat into account, helping the island to resume its natural migration by urging the movement of sediment across the marsh. Starting with a close examination of the natural behaviors of the landscape of Pea Island and its surrounding water systems, the team conducted an in-depth study of inlet and shoal dynamics. The naturally-occuring inlets, a result of storm events and shifting sediment, are vital for recreational boating and maritime trade as they provide access from the mainland to the ocean. To ensure continual use and consistent navigation, regular dredging of the inlets and infrastructural measures — such as the installation of a terminal groin (constructed in the early 1990s)— have been utilized, but these create a fixed barrier that is in contradiction to the changing water landscape.

Riedlinger, along with the team, used drawing methods to learn about the landscape's behaviors and its contribution to the erosion of Pea Island's marsh. In particular, they studied the shoals, mounds and ridges where sediment is deposited. By tracing the edges of the shoal using satellite and aerial imagery from the 1970s to present day, they discovered how the shoal boundaries changed over time, and gained an understanding of short and long-term migration patterns.

This understanding was a critical foundation to provide convincing evidence for the project proposal, which in part includes the placement of sediment used in the regular dredging of navigation channels onto strategic spots on the shoal. Their proposed strategy, which works in tandem with other approaches that address other natural processes such as alluvial drift, aims to guide the shoal's energy through controlled overwash and dredge placement, helping the system build its own elevation.

The new forms that Davis and his fellow researchers are developing as part of the Tidelands project have performative aims: to provide storm protection and to restore habitats, but the capacity for nature-based infrastructure to support recreational and social uses for communities carries the promise for long-term investment and care. “Doing the research to develop infrastructures that are based in natural forms is an emerging paradigm,” explained Davis. “It allows us to conceive of infrastructures as landscapes — not merely as solutions to problems — but as places people experience and care for as part of everyday life.”

Project Credits

NIL Co-Director and Associate Professor

Brian Davis

Project Manager

Ruby Zielinski

Research Specialist

Adrian Robins

Research Specialist and PhD Candidate

Marantha Dawkins

Design Research Intern

William Riedlinger

Supported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Engineering with Nature (EWN) Program.