PLACES JOURNAL'S "FIELD NOTES ON DESIGN ACTIVISM" FEATURES ANDREA ROBERTS + CL BOHANNON

Recently published by Places Journal, a second and third installment of a narrative survey in which several dozen educators and practitioners share perspectives on the intensifying demands for meaningful change across design pedagogy and practice, features contributions by the UVA School of Architecture's Associate Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning Andrea Roberts and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture CL Bohannon.

"Field Notes on Design Activism" asks:

How is the field responding to the interlocking wicked problem that define our time — climate crisis, structural racism, unaffordable housing, rapid technological shifts?

To the increasingly passionate campaigns to decolonize the canon, to make schools and offices more equitable, ethical, and diverse?

What are the issues of greatest urgency?

What specific actions and practical interventions are needed now?

Across seven installments, architects, landscape architects, urbanists, and educators are variously hopeful, gloomy, critical, judicious, exacting. Some doubt whether design, as the profession is now constituted, can be a force for structural change; more than a few argue for the efficacy of collective bargaining and the imperative to work with communities in need of the best that design thinking has to offer, along with the importance of joining political movements beyond the field. All agree there is much to do, and that these struggles will last a generation or more.

In addition to Bohannon and Roberts, School of Architecture alumni Adam Yarinsky (Principal of ARO), Marc Miller (Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Penn State University), and Thaïsa Way (Director of Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks), all contributed to the survey.

Excerpts from their note on design activism are shared below:

CENTERING MARGINALIZED NARRATIVES THROUGH DISRUPTIVE ENGAGEMENT(S)

CL BOHANNON

The pandemic only exacerbated systemic inequalities that disadvantage Black and Brown people and their collective health; it revealed what was already happening. But it also invited a renewed critique of structural racism, by showing in stark relief the omnipresent forces that continue to unjustly affect communities of color. This is not a new understanding of the American milieu, particularly when it comes to landscapes of marginalization. But it does raise a critical question for me as a landscape architect and educator. How might community narratives be used to disrupt conventionalized and exploitative readings of place and people, to steer us towards a more equitable future?

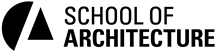

James Baldwin helps us to understand the imperative of hearing such narratives in his 1972 book No Name in the Street:

If one really wishes to know how justice is administered in a country, one does not question the policemen, the lawyers, the judges, or the protected members of the middle class. One goes to the unprotected — those, precisely, who need the law’s protection most! — and listens to their testimony.

Baldwin reminds me that stories play an important role in the development and survival of cultures, providing significant information about language, history, and the environment. Stories and histories can come in textual form, or in visual form (such as maps, photographs, and diagrams), or in verbal form (such as oral histories and folk music). In all forms, they interconnect in our daily lives and contribute to the makeup of our cities and neighborhoods. Communities of color have historically been marginalized in planning and design decisions — decisions that have shaped the very spatial, economic, and environmental conditions under which those communities live — resulting in conflict, inequality, discrimination, and displacement. Going forward, it is imperative that we center such voices and their stories in design decision-making.

This starts with asking critical questions to disrupt the traditional design practices that have built landscapes of marginalization. What does that mean? It means that we attend to power. It means that we call out absences and voids. It means that we are intentional about who is at the table when choices are made about our communities. It also means that we need to understand what is being privileged through the projects we undertake. We need to rethink design from a democratic viewpoint, asking what design is and who has access to it. We need to question what education is and who has access to it. We need to question what community looks like and how it functions. Centering marginalized voices means reimagining the means by which we actualize values of diversity, equity, and inclusion to create a more just and equitable world.

PLACE PRESERVATION: CENTERING PEOPLE OVER STRUCTURES

ANDREA ROBERTS

Historically, BIPOC folks in America and around the globe have experienced many of their calamities in a vacuum, until the next disaster creates another need for response and recovery, which reaches the level of media relevance when occurring on a scale too large to ignore — for example, in recent weeks in Pakistan. As of September 5, 1,300 Pakistanis had died, and millions have been left homeless. The crisis was triggered by years of floods, which had already brought vulnerable drainage systems to the brink of failure

This is happening seventeen years after Hurricane Katrina and the corresponding infrastructural disaster led to the deaths of 1,800 individuals — and five years after Hurricane Harvey submerged the fourth largest city in the United States (including its freeways) — and a year after Hurricane Ida led to almost 100 deaths, nearly 20 percent of them associated with carbon-monoxide poisoning from portable gas generators in homes with inadequate ventilation. Unprecedented floods and freezes in Texas and now Mississippi make it clear that we need to focus more comprehensively on hard and soft infrastructure justice.

If you are experiencing these challenges in your own life, the need to address them is always urgent. I say you because such mass events are often abstracted through news coverage of a distant, victimized other. However, increasingly, the “other” is one of “us” — the designing and planning class living and working disproportionately in coastal cities. Consequently, I speak both to the “you” labeled socially vulnerable and to the rest of us, in denial about how these categories will change and blur over time. Our ancestors have always been adept at designing for a certain degree of resiliency, creating social and physical infrastructures that allow for survival and the ability to rebuild afterward. Such infrastructures — for example, the Black church, benevolent or mutual-aid societies, and places like the 19th-century Brick Streets in Freedmen’s Town in Houston — hold and transfer knowledge throughout communities. This approach to designing for resilience must be foremost in professional designers’ minds, and central to any manuals they — we — reference.

What’s required? Integrating humanities and social science approaches to understanding adaptation. This entails a willingness to engage in ethnographic study, not when disaster strikes but constantly. The most ecologically vulnerable among us are adapting as skillfully as they can; but which of these at-risk infrastructures are already buckling beneath the weight of government neglect, underinvestment, and White supremacy? See Marccus D. Hendricks’ citizen-science approach to infrastructure-equity research. As scholars who speak to the bridging of hard and soft infrastructure, he and I argue that this moment requires tapping into both design innovation (materials and production) and culturally-based adaptation strategies (communication and memory transfer). For too long, governments have operated in endless response mode, lacking proactive study of systemic and historic underinvestment in rural and BIPOC communities. Preparedness-focused research, planning, and practice are essential to addressing the large-scale unrest and multidimensional disaster that will be unleashed over the next two decades because of climate change. When someone is crying out for potable water or scrambling to get to higher ground, it is too late to plan.

Practically, this is about creating visibility for people and places, to permeate planning and design processes that perpetually ignore and silence BIPOC and rural folks until disaster strikes.

An effective manual for design activism should offer guidance not only for responding to crisis but for equipping local engineers, landscape architects, activist planners, and long-term residents to think holistically about place preservation in ways that center people over structures. This is a practice of mapping not only for risk but for place cultures and ecologies.

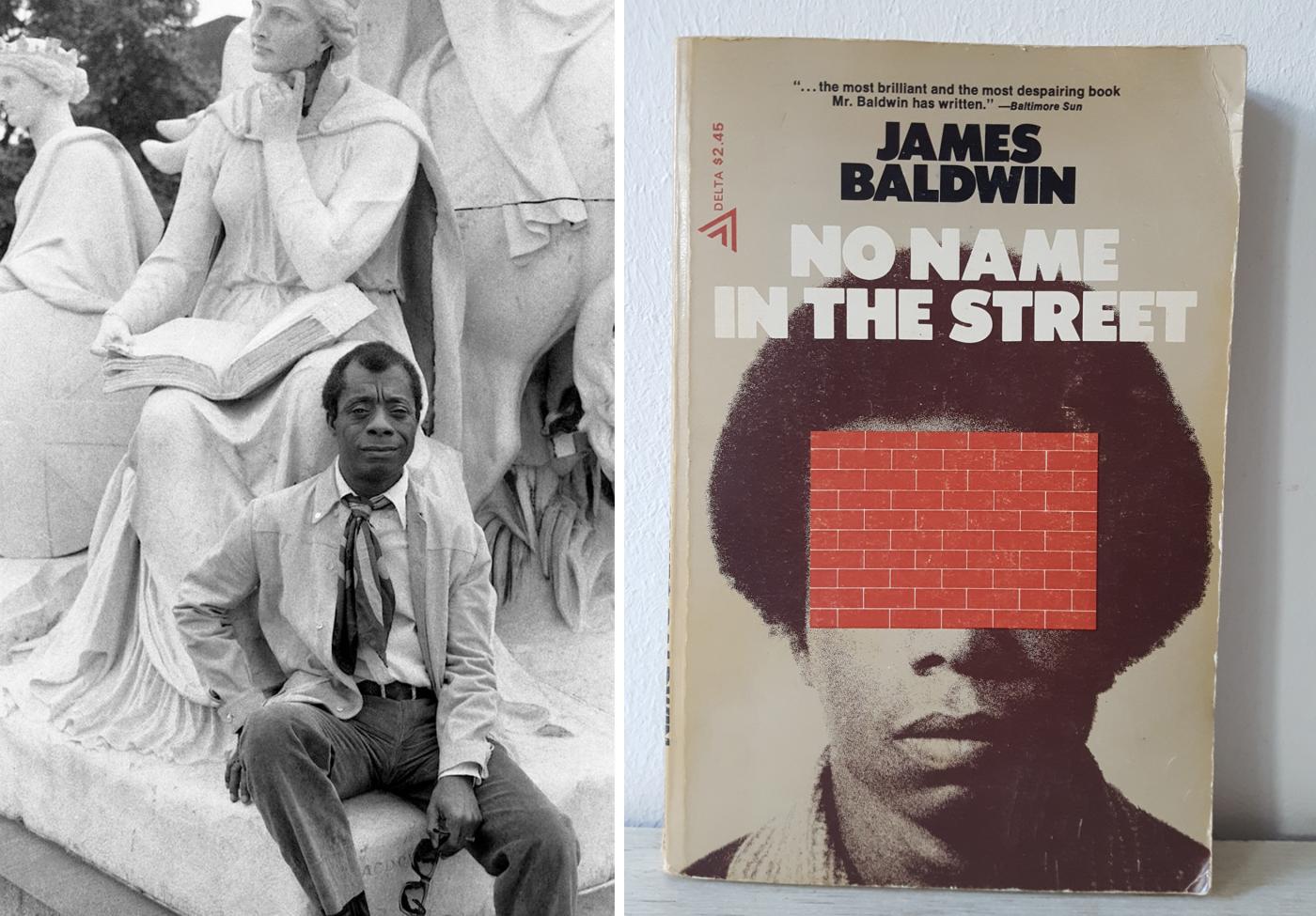

The Texas Freedom Colonies Atlas, for example, maps places in an effort to force any designer concerned with infrastructure justice (or equity) to see the ecologically vulnerable (or advantaged). This conception of preservation requires a maintenance (and stewardship) manual. Such a handbook would not fetishize buildings or romanticize an imagined risk-free past. Instead, such guidelines would call for recording the ongoing neglect and cultural erasure while also spatializing the imprints of Black agency, resilience, and place persistence that have survived in the landscape.

PRACTICE ITSELF AS A DESIGN PROJECT

ADAM YARINSKY

How can the client-driven model of architectural practice more fully engage the urgent challenges of our time, foremost among them climate change and social inequity?

The most important and frequent decision our firm makes (about once a week) is whether we will pursue a potential project. For many years, a key aspect of our mission and business development strategy was to seek like-minded clients. But as social injustice and the climate crisis accelerated in 2020, we realized that we needed to more rigorously assess each new business opportunity in its larger physical and social contexts. This led us to make crucial adjustments to our mission statement and to create a wholistic rubric for vetting new work.

As architects and citizens, we have a responsibility to address environmental and human impacts beyond the apparent limits of our work; our strategic vision to create architecture for a healthy planet and a just society is grounded in an ethos of inquiry, collaboration, and engagement through design. In conjunction with revisions to our mission statement that more fully articulate this vision, our Business Strategy + Communications Director led the development of more robust criteria for evaluating the diverse range of potential projects that we typically consider.

As in the past, this inquiry includes questions about the client, program, site, and budget, as well as possibilities for innovation and research. To these were added questions about the client’s goals and the embedded power structure: who will benefit from, or be served or impacted by the architecture, as well as how it will be implemented. Such questions frame further research by our Business Strategy + Communications team, the results of which are assembled into a concise briefing document. This evaluation process includes assembling a diverse team of consultants. Through this early information-gathering and discussion, we come to understand whether a particular project is right for us, and if the office as a whole and staff members as individuals would be proud to work on it. If so, we are better prepared to respond and, we hope, to be shortlisted or selected. Importantly, this research also helps us to leverage opportunities to address environmental and social issues, even if these are not explicitly included in the brief.

This new framework for business development is consistent with our belief that our practice is itself a design project that continuously evolves through how we shape our methodology and culture. This is one of multiple aspects of our operations that are changing, together with our design work for clients. Many of these initiatives are generated and led by employees, a participatory paradigm that helps our firm to weave together process and projects.

CANON-DIVERGENCE

MARC MILLER

Whitney M. Young, Jr.’s speech in 1968 to the American Institute Architects questioned the efficacy of design professionals’ work in “urban” environments, and to this day when you see this speech referenced, it tends to be part of a call for social change in architecture. Young was, of course, not the only non-designer who has had a transformative impact on the discipline’s concerns and processes. During the 1970s and 1980s, Dr. Robert Bullard — a sociologist — developed the concept of environmental justice. Civil rights leader Dr. Benjamin Chavis coined the phrase “environmental racism” in 1982. Young, Bullard, and Chavis represent three modes of activism, and each figure has had significant effect on designers’ understanding of our public roles and civic responsibilities. Yet we rarely hear their names mentioned in design discourse. Why? Perhaps because we cannot point to objects or spaces they made that we could call “good” or “beautiful” within conventional frameworks for architecture or landscape architecture. They have not added buildings, green spaces, diagrams, drawings, renderings, or photographs to the canon.

It is difficult to document activism after the work is done, because it is a verb and not a noun.

It is nevertheless crucial that we recognize these three figures as critical to the development of contemporary design thinking. In landscape architecture in particular, environmental justice and environmental racism can become big talking points in studios organized around community-based projects. For one semester, students can become activists — making proposals for marginalized places using the same design strategies, technical tools, and image-making habits they draw on for the “non-activist” renderings they’ve learned to make. In history and theory courses, we don’t inform students that Dr. Bullard and Dr. Chavis are still doing the work, and that activism is not a phase or style but a practice. Even inside a design practice, activism is necessarily episodic and requires inventive ways of working with clients, sites, budgets, and more. But if you are committed to making responsible design accessible to everyone, it’s always present, integral to the long evolving arc of your work.

More educators need to become canon-divergent thinkers, recognizing that different students and practitioners have different entry points into the disciplines, and that not all moments or places of historical significance belong to the same lineage. Nor are historical precedents and design strategies always interpreted in the same ways. For example, imagine if someone took the time to look at the emergence of hip-hop in the Bronx as an origin point for what has come to be known as tactical urbanism. We would be afforded another opportunity to understand the impact of hip-hop on spatial practices, such as the block parties where DJ Kool Herc spun vinyl on turntables. Simultaneously, we would gain new perspectives on the role played by capital — or lack thereof — on how the built environment is made and read.

Regardless of the reasons for omission or oversight, designers must see more, see differently, and cite better. We can’t do the work if we don’t recognize the real activists.

REIMAGINING THE ACADEMY

THAÏSA WAY

Change has never been more urgent in our design and planning schools. And yet how do we reimagine the academy?

If you follow the money in alumni and professional associations, scholarships are the sexiest program of the moment; institutions are focused on fundraising and marketing to prospective applicants, suggesting that we just need to enroll a few diverse students and, magically, schools will be changed (for the better one hopes). Yet, while laudable, this is not the most powerful lever with which to dislodge enduring racist, sexist, and settler-colonialist legacies. Students enroll demanding progressive re-envisioning, and it is essential to engage them in the process of achieving it. But, at the end of the day, creating change in the academy is not their responsibility.

It is the responsibility of faculty to productively tackle how we build and share knowledge and practices that engage the intersecting crises of climate disruption, structural racism, lack of affordable housing, and public health. To do this work, we must acknowledge the complicated legacies of design practices and, simultaneously, explore alternatives for the future. For this, we must think differently about who teaches and what we think it means to educate. Accordingly, if there is one strategy we need, it is to invest in faculty. Faculty are at the heart of real and enduring transformation.

This means taking seriously the call for scholars who bring alternative histories and counter-bodies of knowledge, learned and tacit, to the practices and the disciplines of design. At the same time, hiring one Black colleague, a Latinx or Asian colleague, a female colleague, maybe an Indigenous colleague: this will not fix the issue. If we are to steward our schools as places of belonging and engagement with a truly representative array of people, ideas, and places, new faculty must have support from a full community of practice. Every faculty member must undertake the hard work of transformation, whether in teaching, scholarship, or service. We must re-imagine our professions by working collaboratively across schools to mentor underrepresented early career faculty, and at the same time, to learn as communities of practice how to re-formulate our work and our leadership. Only then will we be able to sustain an academy, a curriculum, and in turn, the professions necessary to tackle the 21st-century’s greatest challenges.

Read the full series on Places, an online journal featuring public scholarship on architecture, landscape, and urbanism:

FIELD NOTES ON DESIGN ACTIVISM

AB0UT THE AUTHORS

CL Bohannon is associate dean for justice, equity, diversity and inclusion and associate professor of landscape architecture at the School of Architecture at University of Virginia.

Dr. Bohannon’s research focuses on the relationship between community engagement and design education, primarily through design for social and environmental justice. He works in the contexts of community history and identity, social/environmental (in)justice, and community learning. His research has contributed to the theorization and application of community engagement in design education. Dr. Bohannon teaches courses on community-engaged design, design research methods, and seeing, understanding, and representing landscapes.

Andrea Roberts is an associate professor of urban and environmental planning and co-director of the Center for Cultural Landscapes at the University of Virginia.

Since 2014, she had led the Texas Freedom Colonies Project, which leverages heritage conservation strategies to combat historic Black settlements’ invisibility and environmental vulnerability. Through participatory action research, the project spatializes oral histories and archival material on an interactive digital atlas, making previously unknown settlements legible to policymakers and practitioners. The Vernacular Architecture Forum, Urban Affairs Association, and Whiting Foundation have recognized her work.

Roberts is co-project director of the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Summer Institute “Towards a People’s History of Landscape — Part 1: Black & Indigenous Histories of the Nation’s Capital,” a convening of humanists and social scientists exploring alternative ways of teaching social histories of the founding of the United States and the District of Columbia. She is currently writing a book about oral traditions in descendant community preservation, which will be published by University of Texas Press.

Adam Yarinsky (BSArch 1984)is principal of Architecture Research Office, a New York City firm united by collaborative process, commitment to accountable action, and social and environmental responsibility. ARO’s diverse body of work has earned the firm over a hundred design awards including the 2020 National AIA Architecture Firm Award. The firm’s current and recent projects include the restoration of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, along with a new campus for the organization; the expansion of Dia Art Foundation’s New York City exhibition spaces; two new passive house public schools in Brooklyn; and seven projects nationwide for design leader Knoll.

Marc Miller (MArch 1994) is an assistant professor of landscape architecture at the Stuckeman School at Pennsylvania State University. He is vice president of diversity, equity, inclusion, and recruiting for the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture and the current president of the Black Landscape Architects Network.

Thaïsa Way (MArH 1991) is director of garden and landscape studies at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library in Washington, D.C. She is a scholar of landscape history, theory, and design, teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and professor emerita at University of Washington. Her book, Unbounded Practices: Women and Landscape Architecture in the Early Twentieth Century (UVA Press, 2009) was awarded the J.B. Jackson Book Award. Other books include GGN: Landscapes 1999–2018 (Timber Press, 2018), The Landscape Architecture of Richard Haag: From Modern Space to Urban Ecological Design (University of Washington Press, 2015), River Cities/ City Rivers (Dumbarton Oaks and Harvard University Press, 2018), and, with Eric Avila, the forthcoming Segregation and Resistance in American Landscapes (Dumbarton Oaks and Harvard University Press, 2023).