Generative AI Contributes to Landscape Architecture Students' Design Process

As the Chesapeake Bay’s coastal landscapes and islands stand on the frontline of climate change, the graduate Landscape Architecture Foundation Studio IV (LAR 7020) “Prototyping the Bay: Landscape as Medium,” taught by Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture Brad Cantrell, is pioneering a bold experiment. Here, the Pocomoke Sound becomes a living laboratory, where the land itself is an active participant in research and knowledge production. This studio is reimagining the landscape as dynamic entities that respond to and inform our strategies against the encroaching tides of change.

A few weeks ago, the studio presented mid-review work developed in part from a course module, called “Narrating Opportunities.” The module introduced students to tools for exploring image creation, patterns, and simulations. Across several workshops, students gained deeper knowledge about artificial intelligence (AI) image generating technologies like MidJourney and Stable Diffusion, and captured videos and image sequences of land and water patterns modeled on the school’s geomorphology table. As a result, the mid-review showcased an exciting range of video and AI-assisted speculative narratives that helped visualize and analyze the future of ecological resilience.

Embedded within this course’s innovative approach is a critical reflection on the ethics of AI creation. As teams harness Generative AI to craft images and videos that depict potential futures, they are also tasked with thinking how to attribute the intellectual labor behind these models. It’s a challenge that asks: How do we credit a machine’s output, and what does it mean for the future of creative authorship?

Eric Field is Director of Information Technology and a lecturer at the School of Architecture who often teaches courses on data visualization. In his opinion, getting people to respond to AI technologies honestly, meaningfully, and thoughtfully is perhaps the most significant pedagogical challenge that we face right now. “I’m hoping to embed some generative AI prompting into a few of our introductory design courses, working with the faculty to get us to really test this, push it’s envelope, see what it can and cannot do, and reflect on that directly within the context of a class on how and what we make, including the ethics of those things,” said Field.

The LAR 7020 studio sets the stage for a profound exploration of how we interact with our environment and the tools we use to understand it. It’s a story of landscapes that are not just seen but are deeply felt and interacted with, as they become the early warning signs for our planet’s health and our own adaptive capacities.

Several of the graduate landscape architecture student teams shared more about their projects and weighed in on the challenges and opportunities of using Generative AI in the design process.

EXPERIMENTAL LANDSCAPE: MITIGATIONS, MURMURATIONS, METADATA

SAMANTHA HUBBARD (MLA '25), MAYA NEAL (MLA '24), PAIGE WERMAN (MLA '24)

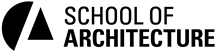

SH: Our landscape experiment [Irish Grove Wildlife Sanctuary] aims to amplify how continued landscape engagement can foster better understandings of symbiotic relationships between humans and non-humans in our shared world. Our particular goal is to engage the land as a laboratory to explore how habitat gradients and climate migrations will continue to impact avian migrations.

MN: While foundationally we utilized scientific studies, historical databases, and geospatial research tactics, generative AI played a big role in visualizing our synthetic narrative between humans, birds, and technology.

PW: Since these [AI] tools are especially new to research projects and the extent of their reach is still becoming understood, I think a primary challenge and call to action that this studio demands is a way to cite these sources. Citing them became a process for understanding where the machine learning tools were drawing their imagery from. We also began to recognize the inherent biases that the tools have due to the biases of the internet and the types of data, images, and writings that are readily and more widely available. For example, when writing “scientist” the tool automatically represents a white male.

THE CITY OF CRISFIELD: SEAFOOD CAPITAL OF THE WORLD

JOYCE FONG (MLA '24), JULIA MACNELLY (MLA '25), LYSETTE VELÁZQUEZ (MLA '24)

JM: The city of Crisfield, Maryland, is a small city of around 3 square miles, 2,500 people, and 50% of water surface. The sea level rise severely threatens it, and its history is deeply tied to the bay's waters. Learning about Crisfield raised questions about how the dynamics of value, labor, and ecological change can shape a place.

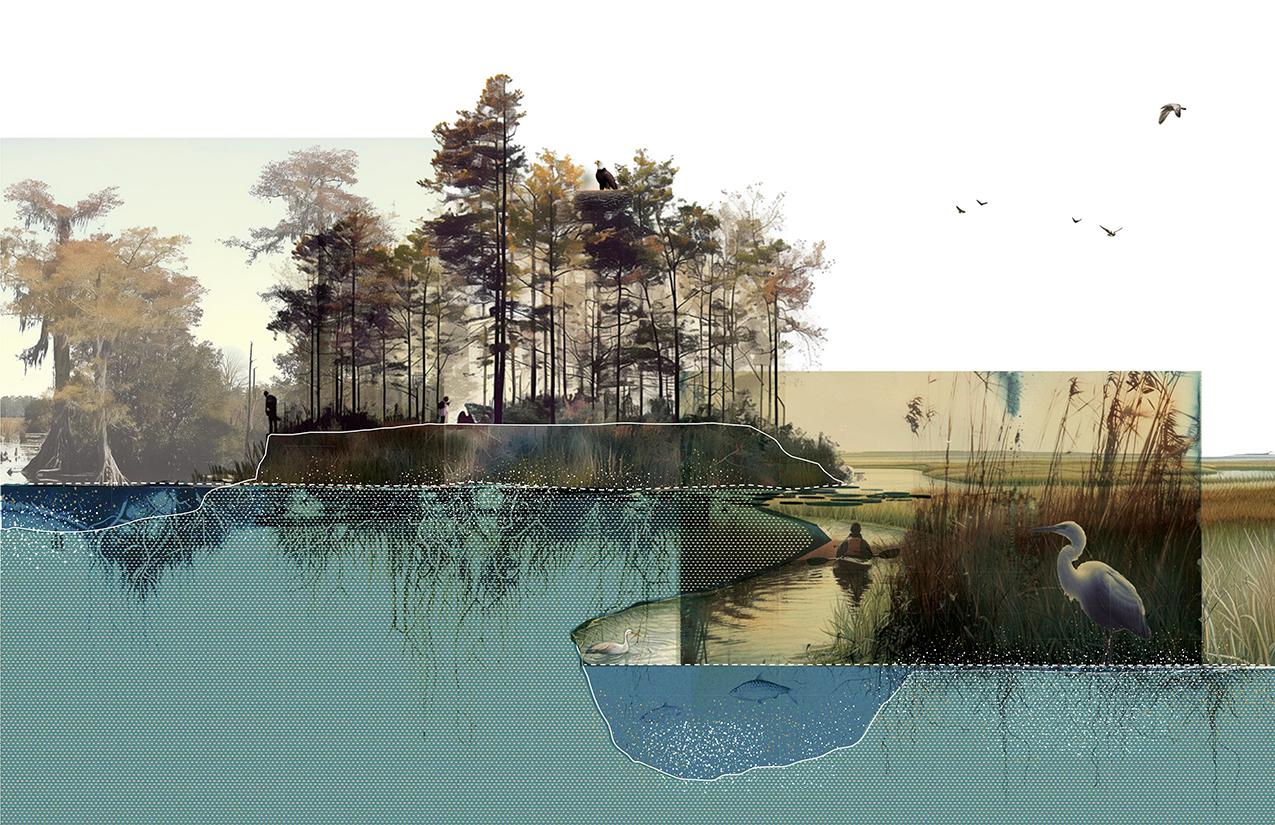

JF: In the face of a rapidly changing coastline, we confronted the challenge of devising zoning systems that reflect the instability of our environment. The traditional zoning approach falls short in addressing rising sea levels and shifting coastlines. Instead, we proposed an adaptive and organic zoning system that mirrors the dynamic nature of the land. Inspired by the resilience of marsh ecosystems, our vision is for a zoning system that embraces fluctuation and diversity.

LV: AI is a powerful tool capable of simulating a dynamic and ever-shifting reality. We found this fluidity compatible with the dynamic nature of the landscape itself. Using these tools, as well as an awareness of ecology, we had the idea that zoning itself could be more dynamic, reflecting organic and human-made principles.

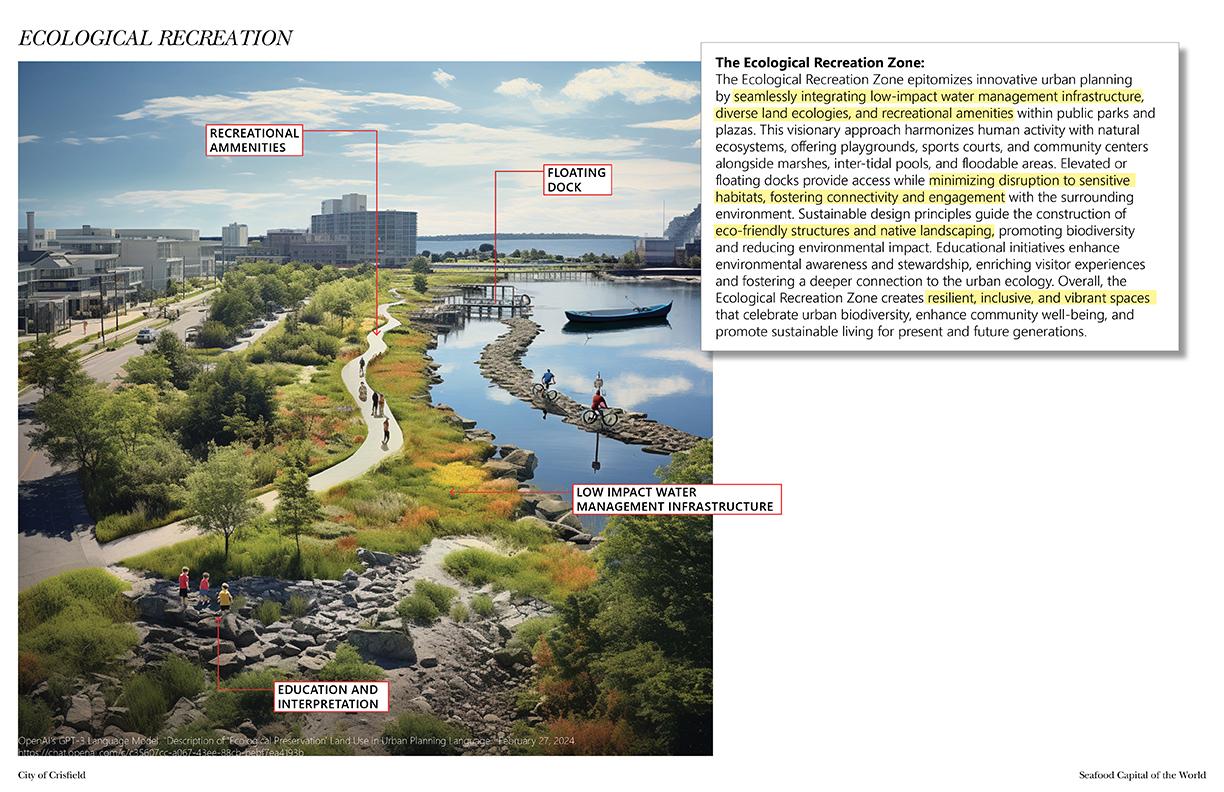

JM: MidJourney produced a series of images that seem to interpret marshland as dirty, messy, and unruly. AI generates images from what already exists, and the images don’t always reflect the imaginative prompt language of a proposed scenario.

EXPERIMENTAL FLOW

MARY COTTERMAN (MLA '25), ANSON TSE (MLA '24), STANIE ZHANG (MLA '24)

MC, AT, SZ: In this project we look at the effects of concentrated animal feeding operations specific to chicken waste runoff into the watershed and how it affects the life of the area. Ditching, dredging, and industrial agriculture have caused an increase in the speed and flow of water down the river to the bay, while simultaneously lowering the groundwater table by preventing slow flows and infiltration of water. This has sped up the rate at which nutrient runoff gets into the water, and prevents it from being broken down in the microbially active layer of the soil.

We imagine a grass roots, human scale system of land modification, like the one that created the landscape as we know it now, but instead with an ethos of reciprocity. This could look like resident participation in ecological care through hands-on maintenance, land modification, and citizen science that systematically makes space for the agency of the non-human.

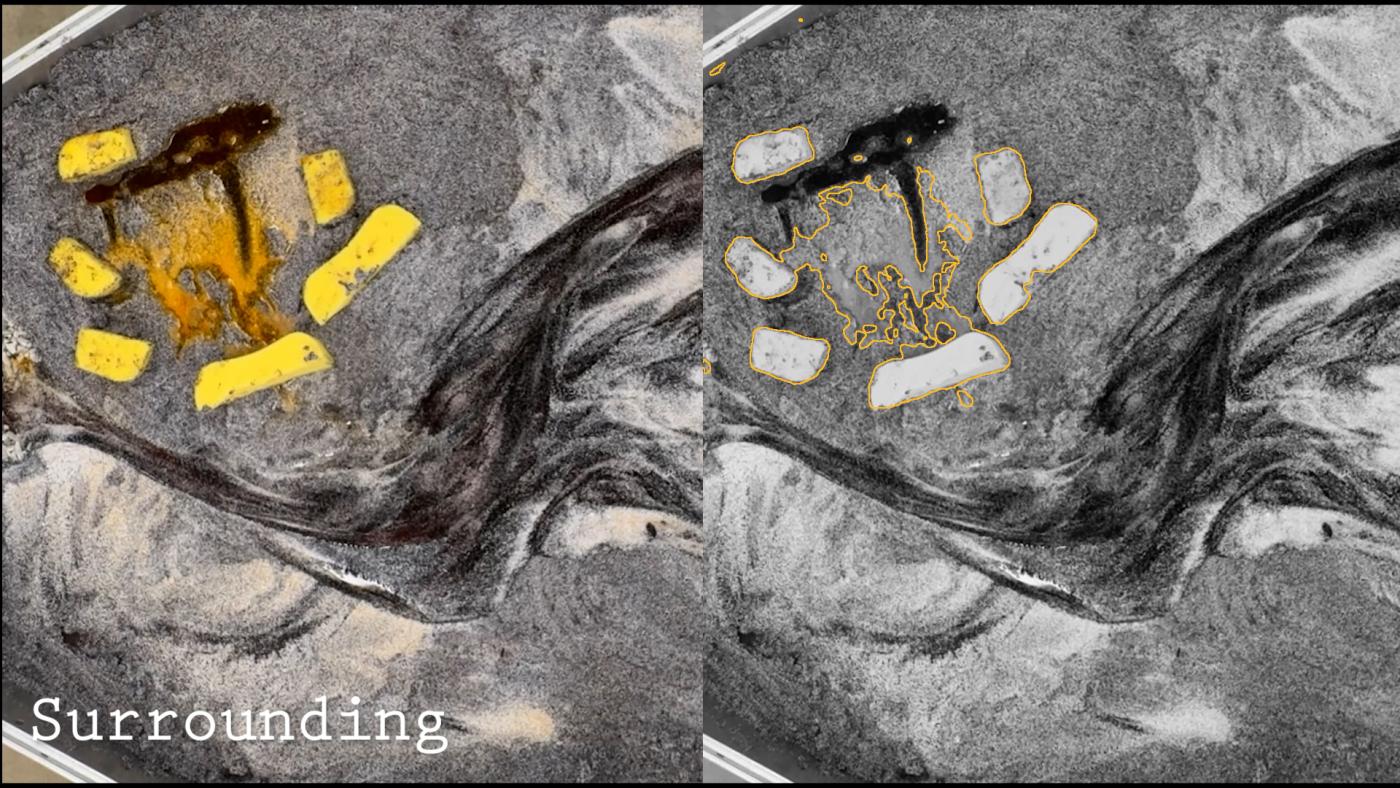

In documenting our runoff modeling experiments, we utilized stream diffusion to process the video of our prototypes. This allowed us to pull out certain colors and quickly edit and overlay. It also allowed us to generate edge shapes to visualize the flows of runoff through sediment and modeled wetlands.

Students’ attitudes toward generative AI are multifaceted, reflecting both optimism and caution. After asking the students on the above three teams to rank AI on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being “most threatened” and 10 being “most excited,” the results fell squarely in the middle. Joyce Fong acknowledged the potential of generative AI tools to create unconventional and inspiring images. “However,” she said, “ethical concerns arise when these tools replace traditional creativity. The balance lies in how we wield them.”

In this complex landscape, students grapple with the promise and pitfalls of AI, seeking a harmonious integration that amplifies the design process.

LAR 7020 Teaching Faculty

Brad Cantrell, Professor and Chair

Lauren Cantrell, Lecturer

Isaac Hametz, Visiting Faculty

Sean Kois, Lecturer

Sophie Maffie (MLA '24), Instructional Assistant