Biophilic Cities Publishes Strategies to Value and Retain Mature Urban Trees on Private Lands

This spring, PBS’s Virginia Home Grown aired its first episode of season 25, “Big Old Trees.” The series host Peggy Singlemann, Principal, RVA Gardener, visited Maymont in Richmond, a historic park that stewards many state and national champion trees. Champion trees are the largest known of their particular species within a specific geographic area and are examples of enduring growth and, often, maturity.

Big, Old Trees

Maymont, a 100-acre green space in the heart of Richmond, was originally the home of James and Sallie Dooley. The park has trees that go back to the original estate which was established in 1893. These majestic trees continue to face challenges since the property use shifted from a private estate to a public park over its more than century long history —but as Sean Proietti, the property’s Senior Manager of Horticulture and Grounds, explained, “With old trees, the main thing is to not do anything that shocks them.”

The park invests in a variety of care techniques by specialists to preserve these mature urban trees. Prioietti described, “This is a place that is irreplaceable, in our history, it’s part of our culture, it’s part of our economy.”

The episode later takes viewers on a tour of the Dragon Run on the Middle Peninsula to learn about its bald cypress trees and old growth forests — where some of the trees are estimated to be over 1,000 years old. Jeff Wright, president of Friends of Dragon Run, a nonprofit that promotes the protection of this significant Chesapeake Bay watershed, identifies multi-century trees located there and shared, “It’s amazing to know how old these trees [are and how long they] have been here — and what they have seen in Virginia’s history.”

Why Protect Mature Trees?

PBS’s “Big, Old Trees” brings attention to the value of mature trees, and in the case of Maymont, within urban centers in particular. While the show’s episode featured a city park and nature preserve in Virginia that are both, for the most part, publicly maintained, education and policy on the protection of mature trees on private lands is critical to positive benefits to human and environmental health. These includes providing animal habitats, reducing urban heat, sequestering carbon, mitigating stormwater runoff, and reducing stress levels.

|

Image

|

Authored by Timothy Beatley (Director of Biophilic Cities and Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities at the University of Virginia School of Architecture) and JD Brown (Program Director, Biophilic Cities), the newly published policy advisory “Strategies to Value and Retain Mature Urban Trees on Private Lands” explores strategies to preserve mature urban trees — those that have reached their maximum size and height according to their species and the urban environment they inhabit. The policy advisory is accompanied by an online toolkit that will continue to be developed with new and updated strategies by the newly formed Center for Forest Urbanism at the University of Virginia School of Architecture.

Beatley and Brown articulate how research has documented the specific positive contribution provided by older, mature trees, which generate greater benefits than newly planted, younger trees. During this stage, trees are the most productive, offering greater ecosystem services and biophilic benefits for health and well-being compared to newly planted trees.

Moreover, when mature trees are lost, their benefits are lost with them as re-planting programs are susceptible to the high mortality rates of newly planted trees and high costs. The policy cites that the consistent level of disturbance caused by turnover in the built environment and land uses on private urban lands has come at the cost of retaining mature trees. As of 2018, the US Forest Service estimated an annual loss of 36 million urban trees per year or 175,000 acres annually.

A Four Step Policy Roadmap

“In the urban context, mature trees provide outsized contributions in terms of the ecosystem services and biophilic benefits for health and well-being that they provide,” said co-author Brown. “Despite their benefits, the retention of mature urban trees is undervalued in current policy. Through this project, we sought to identify and share existing policies that are addressing this disconnect.”

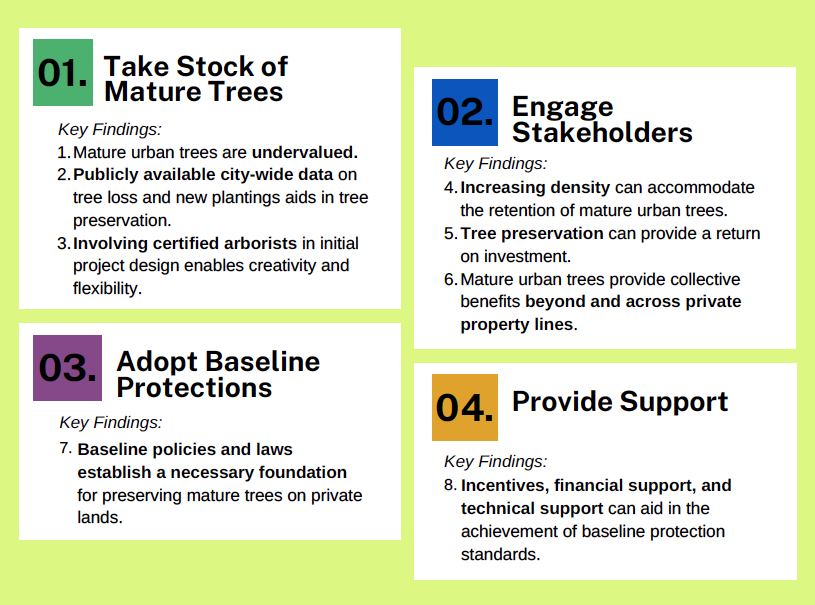

The policy advisory advocates for cities to take four steps to preserve mature urban trees. The first three steps create a foundation for tree protection and include: 1) assessing the state of existing mature trees, 2) taking meaningful steps to engage stakeholders, and 3) providing a regulatory baseline to ensure that mature trees are protected. The underlying fourth step involves: 4) the creation of mechanisms to support private parties in achieving these protections through incentives and financial and technical support.

All of these steps have been implemented by various localities but rarely comprehensively to address all four steps to effectively communicate, evaluate, and track progress towards the preservation of mature trees on private lands. For each step in the policy, key findings are summarized that aim to compile diverse ideas and innovative examples to help protect mature urban trees.

Brown elaborated, “We found that an effective policy approach is one that balances regulatory mandates that spur tree preservation with a range of incentives, financial and technical support to help private parties achieve those mandates.”

|

Image

|

|

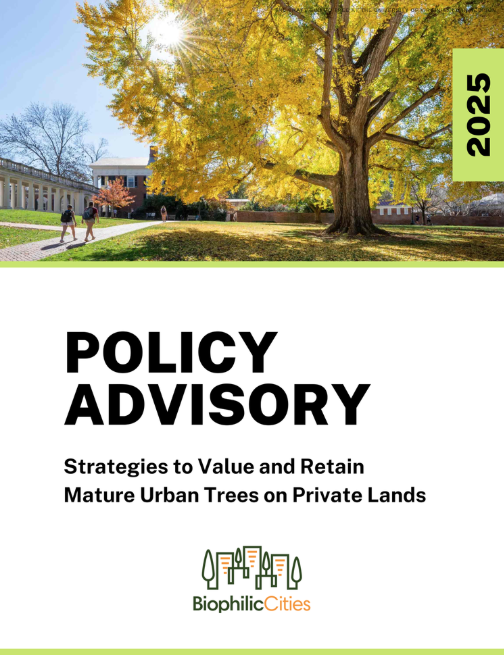

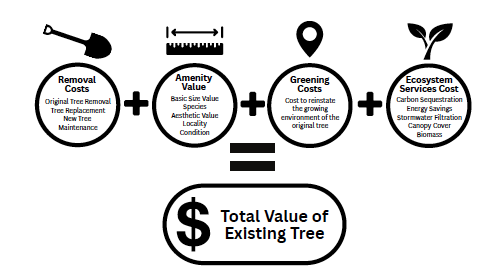

| Diagram based on City of Melbourne Tree Valuation Method created by the Center for Forest Urbanism. | |

The policy advisory and online toolkit work in tandem to provide critical resources and policies that cities can use to address the disconnect between the high value of mature urban trees on private land and our current failures to retain them.

“Protecting existing older trees on one’s private lot… is a civic act of contributing to the larger public good and to the welfare of the broader neighborhood and city in which one lives. Mostly today, how you decide to use or treat the trees on your parcel (and in many cities 60% or more of the trees can be found on private property) is understood as a private matter, not one that you think of the impact of your action on your neighbors and the larger public,” wrote Beatley in his publication Canopy Cities (Routledge, 2024). “But these so-called private decisions do impact the larger good — individually and cumulatively these affect how hot a neighborhood or city is, how walkable it is, and how full of birds and wildlife and thus how delightful and uplifting it will be. Saving that tree, or trees, stewarding over them and caring for them is understood as a form of commitment to the larger community of which one is a part.”

Acknowledgments:

This policy advisory was made possible with funding from the Bob Skiera Memorial Fund. A special note of thank you to participants in the Forest Urbanism workgroup of the Biophilic Cities Network for their insights on the policies and practices underway in their cities. Members of the workgroup included Clarissa Boyajian (City of Los Angeles), Ryan Delaney (Arlington County), Jim Dymkowski (Austin), Keith Mars (Austin), Rachel Malarich (City of Los Angeles), Simon Needle (Birmingham, UK), Mike Reynolds (Reston), Jon Swae (San Francisco), and Tiffany Taulton (CONNECT, Pittsburgh). A team of University of Virginia School of Architecture students provided research assistance, including Jess Newberg, Maggie Ayers, Mai Friedman, Nishat Tasnim Maria, and Gordon Miller. For a more extensive discussion on many of the ideas in this advisory, please read Tim Beatley's Canopy Cities.