Stacy Scott on Identity, Memory, and the Architecture of the Caribbean

Assistant Professor Stacy Scott is a designer, researcher, and educator at the University of Virginia School of Architecture, where she is a member of the inaugural Virginia Architecture Fellowship Program. Her work explores the intersection of design and social impact, challenging conventional norms to create inclusive spaces that reflect the diverse identities of their inhabitants. Now in her second year at UVA, Scott shares insights into the ideas, inspirations, and personal links that guide her research and design practice.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Can you elaborate on the key themes of your work?

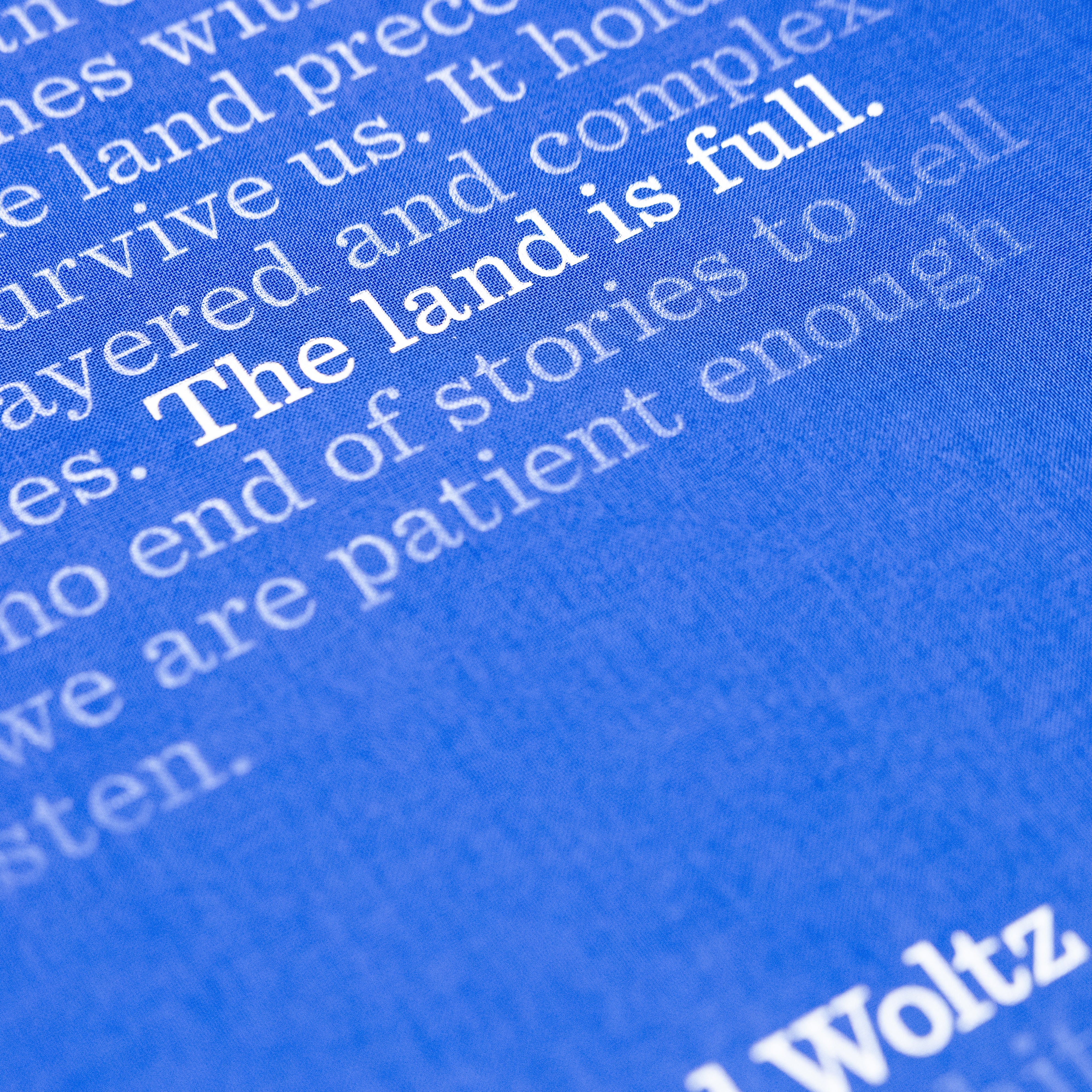

My work feels like a personal exploration because of my deep connection to sites in the Caribbean. I focus on how architecture becomes a source of memory, identity, and resilience, especially in my home country of Jamaica, which has such a layered and fragile history. My research examines how the legacies of colonialism, migration, and environmental vulnerability are woven into the physical spaces that people create.

I spend a lot of time thinking about how these histories shape the everyday spaces people build for themselves. My work is about uncovering those intimate and collective stories. I am also fascinated by how Caribbean diasporic communities in North America create hybrid spaces that bridge the past and present, navigating the ideas of home and belonging.

Your research methodologies reflect a deeply personal relationship with the people, places, and histories of the Caribbean and its diaspora. What does your process look like?

My research methodologies vary depending on what kind of data I’m gathering. I do a lot of ethnographic research, which typically involves sitting in spaces for extended periods and observing how they are used. This quiet, reflective process allows me to see the rhythms and patterns of daily life that often go unnoticed in more structured studies.

I also rely heavily on interviews. Preparing for them can be a lot of work, and it’s amazing how much needs to shift as you learn more, but the conversations that emerge are invaluable. Hearing how people feel and interact with their surroundings grounds my work in reality—it’s more than what can be captured in quantitative data or surveys.

The interviews are a reminder of why this work

is so interesting and important.

How do different mediums and source materials shape your research and deepen your connection to the human experience in architecture?

The wide range of sources I draw from is the most fun part of my research! Photography is a considerable influence for me—especially images of everyday spaces. I have amassed a collection of slides showing pre- and post-disaster conditions of important landmarks and domestic spaces in the Caribbean (and culturally Caribbean places like coastal Panama). There is so much to learn from the textures of the film, the wear and tear, and how people leave their mark on a place.

I also lean heavily on literature—writers like bell hooks, Witold Rybczynski, Jane Jacobs, and Alain de Botton have been instrumental in shaping how I think about space and identity. Their work pushes me to consider the emotional and social dynamics at play in the spaces I study.

But the most important source for me is oral tradition. The generational stories passed down through my family are like an archive of how people relate to their spaces and each other. These stories are fundamental to my work, providing insight into how people shape their ideals and live them out in the spaces they create.

In last spring's Virginia Architecture Fellows Showcase you examined the "front room" in Jamaican domesticity. What is the symbolism of this space and its broader implications for cultural identity and social health?

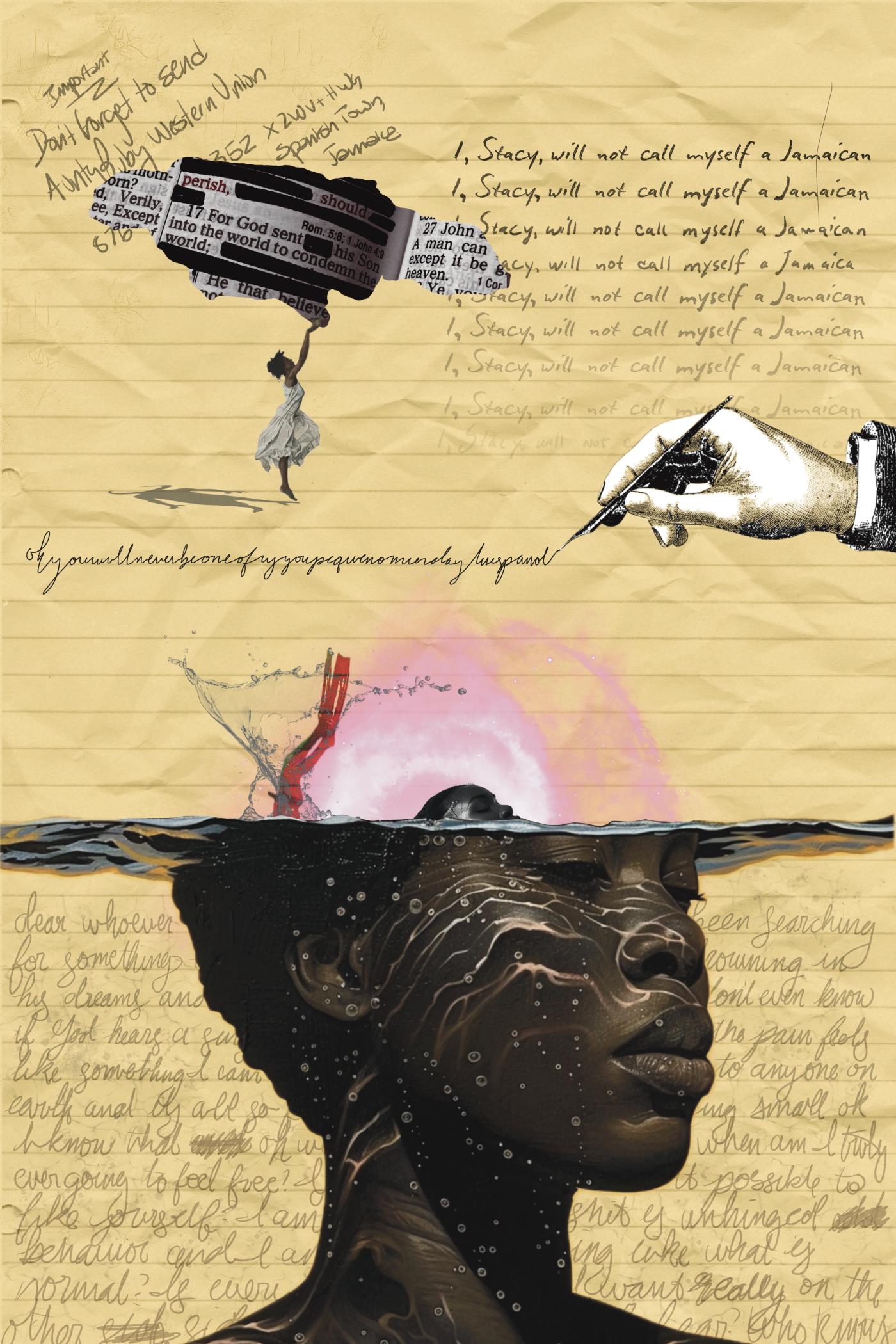

The "front room" in Jamaican homes, for both diasporic and resident Jamaicans, has historically been a significant and culturally loaded space. It operates as a symbolic threshold between public and private life, a meticulously curated area that acts as a stage for the family’s best to be displayed to guests. This space blends native cultural practices with colonial influences from Spain and Britain, becoming a repository of memory.

The objects in the front room—photos, heirlooms, cultural motifs, and furniture—are its lifeblood. They tell the story of family history and continuity. The front room's spatial material culture is a negotiation between public and private, aspiration and ideals, and it reflects the strong Jamaican value of respectability. On a broader level, the front room highlights issues of social health—how people preserve their identity and manage societal pressures, especially within diasporic and post-colonial contexts.

Liminality is a recurring idea in your teaching and research. How do transitional or liminal spaces act as sites of meaning and metaphor in your work?

Liminality is crucial for me, particularly as someone who straddles multiple identities. As a first-generation American, I come from stories of displacement and resilience. My ancestors were part of the wave of Jewish refugees who fled Spain and Portugal during the Spanish Inquisition in the late 15th century, finding refuge in the Caribbean, including Jamaica and Panama. There, they rebuilt their lives and identities far from persecution. These stories have been a profound part of my understanding of liminality, which I define as the experience of navigating between two or more worlds.

For me, liminality represents the space

between my heritage and my current context.

I am constantly negotiating cultural identities and choosing which parts of myself to bring forward in different contexts, like finding the right key for a lock. In architecture, liminal spaces become more than just physical transitions—they symbolize balance, change, and those critical in-between moments where new identities and meanings are formed.

...

The Virginia Architecture Fellowship at UVA School of Architecture supports emerging design practitioners and educators, with a focus on developing creative research and pedagogy at UVA.

|

Image

|

About Stacy Scott

Stacy Scott, a Virginia Architecture Fellow at the University of Virginia School of Architecture, is a designer and researcher whose work bridges architecture, health, and cultural identity. She focuses on fostering resilience and inclusivity in the built environment, particularly within communities of the Caribbean diaspora.

Project Team

Lead Researcher: Stacy Scott

Student Research Assistants: Cole Rozwadowski, Lina Hu, Lola Garvie, and Rosie Wang

Key Resources / Research Support

Michael McMillan, The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home (Lund Humphries, 2023)

Dr. Patricia Green, PhD, Research Fellow, University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica