Alum in Action: Chris Cornelius on the slow practice of studio:indigenous

|

Image

|

|

| Chris Cornelius. Courtesy studio:indigenous. | |

Chris Cornelius (MArch '00)

Professor and Chair, University of New Mexico School of Architecture + Planning

Founding Principal, studio:indigenous

Founding principal of studio:indigenous, alumnus Chris Cornelius (MArch'00) is a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. His practice creates architecture and artifacts that dismantle stereotypes surrounding Indigenous design and offer a distinct vision of contemporary Indigenous culture. Cornelius is also an educator — he is professor and chair of architecture at the University of New Mexico School of Architecture + Planning. Currently, he is a member of the A-School's Dean's Advisory Board.

Recently, Cornelius sat down with Assistant Architecture Editor of Brooklyn Rail Anoushka Mariwala for an extensive interview where they "spoke about maintaining a magic in architecture, finding a language to talk about objects, and developing ways to share that are stripped from a compulsion to fully know and exhaustively understand." In it, he shares how his experiences as a graduate student at UVA School of Architecture, in part, shaped his practice and his methodology.

Below we share an excerpt from this illuminating Q+A.

Access the full published interview by Brooklyn Rail here.

Anoushka Mariwala (Rail): How do we talk about your work? I don’t even have the language or vocabulary that it takes to talk about everything that you’re trying to do, the way you move through the world with such intentionality.

Chris Cornelius: I remember distinctly when I was in graduate school thinking to myself, “What is it that I want to do?” One was that —

I wanted to create spaces—buildings at that time—for Indigenous people that really reflected the culture, and in that, create the contemporary artifacts of the culture.

If my ancestors came back from the seventeenth century, and they saw a longhouse (our people are traditionally builders of longhouses) that was built out of concrete, I feel like they would just be like, “Well, what did we suffer for? Is this all we got?” The other was really just as a professional. Someone like Douglas Cardinal, who was really the only Indigenous architect that I knew, and someone that had built his own career and created his own voice, wasn’t replicating any sort of Indigenous forms, but he was using Indigenous values in the work. That’s what I wanted to be.

The dream is if another project, like the National Museum of the American Indian, came up, they would say, “We have to have Chris Cornelius design this.” That’s the goal.

I don’t even think I’m quite there yet, but that was the thing that was driving and compelling me, because I knew I had to be a good architect and designer first. No one was going to listen to what I had to say unless I was, which is happening now.

_________

Rail: A big part of this desire, what you’re preparing for, is confronting, rather than turning away from, non-Indigenous environments. You talk about being a good ancestor, but I also think that the way you think about yourself as a descendant of the practice of architecture is a refusal and negotiation with the profession, with what you’ve inherited. You’ve been very deliberate about confronting and entering systems that have historically obstructed or rejected Indigeneity, both as a designer and as an administrator.

Cornelius: I don’t think that Douglas Cardinal was the Indigenous guy, and I didn’t want to be that either—to let that define who I am. It happens in architecture a lot: there’s a sustainability person, there’s a museum person. I didn’t want that kind of sort of moniker identifying my work.

UVA was the thing that changed my life. I felt like they taught me how to think about the world, and my teachers respected me as an Indigenous person. I should pull out my application essay, because it’s more like a manifesto, really. I didn’t know how to do it then, and school gave me the tools to do it. But at the same time, like, things didn’t just happen overnight. I just felt like something was pushing me forward.

I had always just thought about my grandmother and my ancestors, even my father, and I know that they had struggles that were real. But I also understood that these people were counting on me. I understand that if I’m going to do what I’m saying I’m going to do, I need to do that thing right. It was years before anyone really started paying attention to what I was doing. I knew that if I wasn’t prepared for that moment, it wasn’t going to really happen. What I really want to do is get people to think about Indigeneity differently, not in a historic way, as if it’s in the past. There’s remarkable attention towards all Indigenous creative people today, and I’m happy to be a part of it.

With teaching, I knew that if I didn’t do it, no one else was going to do it. No one else was going to be able to give this sort of content to others. These institutions I’m teaching at have begun to open up, and they are doing something by inviting me to do this work. I take that responsibility very seriously.

What I’m doing is not just about Indigeneity. It’s about methodology.

_________

Rail: I think part of the way I understand your practice is in language. There are models, photographs of models, drawings, and then the way you speak, which is this whole other thing that is necessary to enter your world. And now, we also have this manifesto that you have written, which seems like the very beginning of your thinking via words.

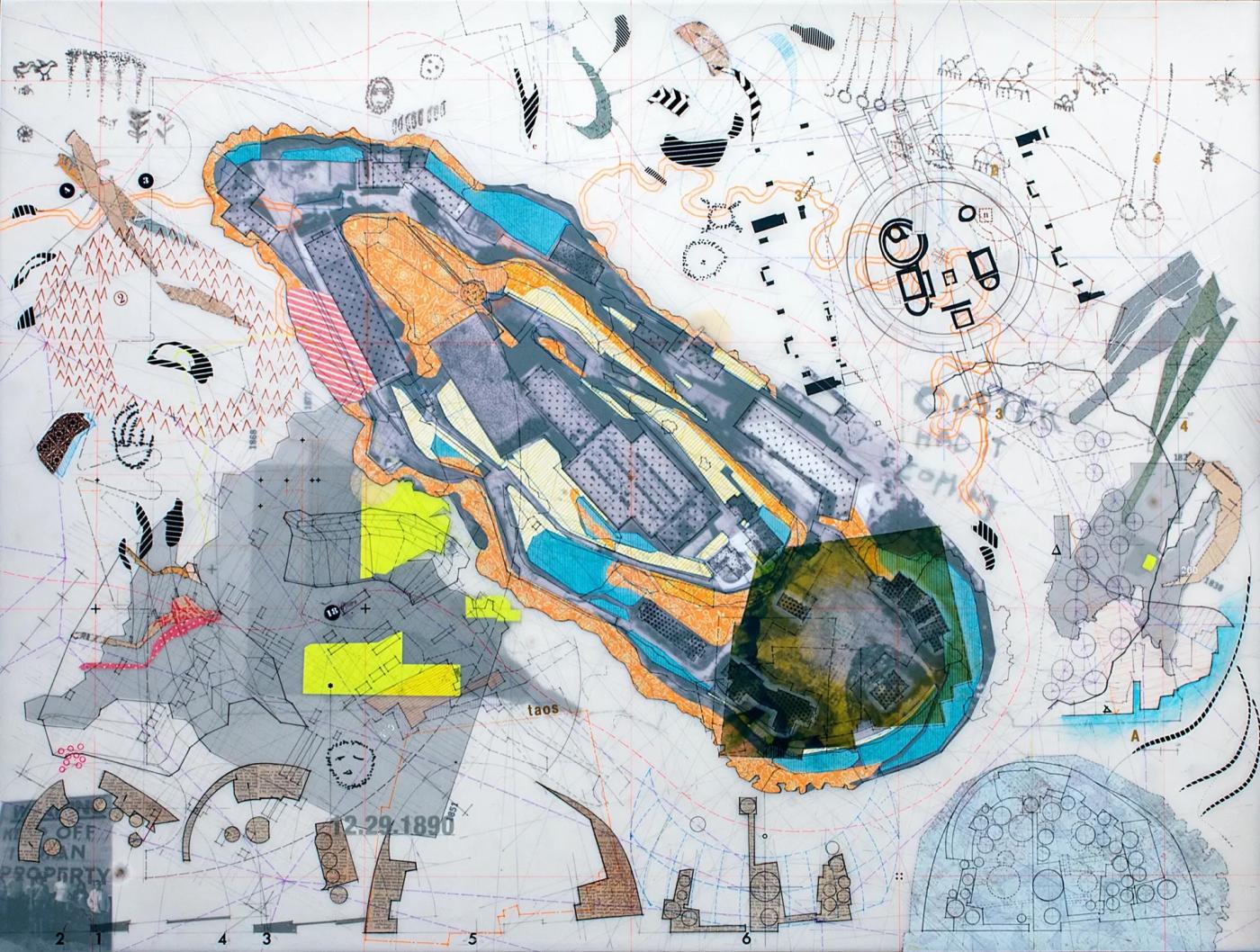

Cornelius: I think it’s valid to see it that way, because it is true. I find writing laborious; I don’t think that I’m good at it. When I presented my graduate thesis project, I had it all up on the wall, and I sat down at three in the morning when I finished pinning it up, and I thought, “How am I going to talk about all this?” I decided to talk about it in a sort of narrative way.

I’m really fascinated by narrative, in that it starts somewhere, it builds on something, and is not just a linear thing.

I think about this a lot when I’m making things, which helps me talk about them, when I’m not even sure where something came from. The drawing is mostly for me, it’s my research. If people think it’s a wonderful artifact, that’s fine. The parallel, though, is that is exactly how I think about architecture. I’m trying to make a beautiful thing that someone’s going to look at and say “That’s a nice thing,” whether or not they get the story. It’s okay if you don’t.

My thesis paper was largely based on Roland Barthes, because I just got fascinated with this idea of the sign and the signifier. This is what happens in my culture with iconography, with things that stand for much more than what it is. That’s where I value my architectural education. It’s just that we have to augment this type of knowledge with other points of view, which is the thing that architecture schools have not been doing.

_________

Rail: Architecture, I am discovering in practice, is so wrapped up in being rational, and it is consistently demanded to answer questions and justify its being in ways that are ungenerous and less exciting. What can we do?

Cornelius: When I started pursuing architecture, I was really compelled by those things. I really love how buildings are made. I really love drawing these things, doing construction sets and learning how things go together. Another thing that I learned [from working with architect Antoine] Predock was that the project had a budget, and we did “value engineer” things, but the decisions that were made to do that were based on the values we had established in the design already. In changing this thing from this material to this one, are we losing anything? No, so it’s okay.

What you don’t see are all of the health clinics in Wisconsin that I designed. You don’t see all of the high school additions I designed. You don’t see the fifteen houses I designed on my own reservation. You don’t see all of that. And there’s a reason I don’t show it to you, because it doesn’t help. It doesn’t help advance what I’m trying to do or what I’m saying. So it doesn’t exist. However, it’s all experience that I have to be able to do what I do now.

_________

Rail: The ability to think in an extended X-axis of time, and a deep Z-depth, is something I feel you have an intense muscle for. I have to struggle to not think in a line. It makes me think that the dexterity to be able to do it, but also to translate it into some material form, is so special, where I think the three-dimensional is already in the thinking.

Cornelius: Architecture school can ruin that for us sometimes. Within the past few years, I’ve started to really realize how much of my life as a very young person has to do with the way that I think now. Without giving too many details about how I grew up, on the reservation, there was an entity in our community. I won’t say what it was, because that’s not actually what's important here. That entity had a home in the woods, and so when we rode our bikes by it, we rode faster. And my heart started pounding faster, or I would start sweating, or I decided that I’m not going to look directly at that thing. What I didn’t realize was that is the power of architecture. Architecture is doing that to me. I’ve always thought about that thing when I’m building models, when I’m making drawings. I’m thinking, “How do I articulate that? Can I do that for someone else? Can an architecture still have that response?” It’s completely uncontrollable, because it’s just about experience.